Writing & Press

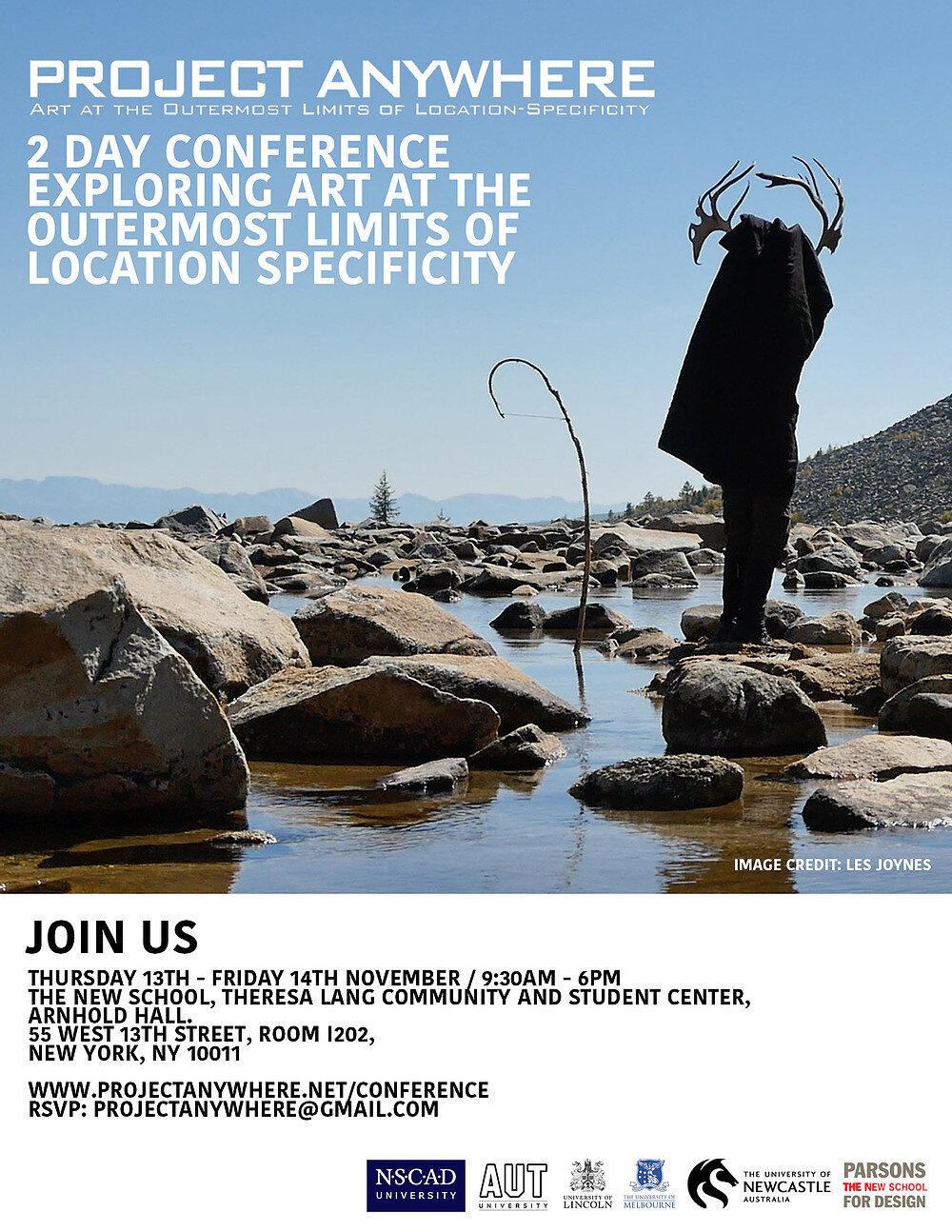

Dr. Les Joynes (US) is a contemporary artist, art critic and curator based in New York. He is recipient of the Fulbright-Nehru Professional and Academic Excellence Award and is a Senior Scholar at Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, New Delhi researching Indian contemporary art and visual cultures. First publishing in 1990, Les began contributing art criticism in 1997 and has written for Art in America, Flash Art, and Springer and recently contributes on artist-centric museums in China’s Cultural Landscape by Mid-Century (Long Museum, Shanghai). Trained in art history and contemporary studio practices, Les recently reviews new creative practices for the Journal for Artistic Research (JAR). He is one of the founding editors of ProjectAnywhere, a peer-reviewed journal at University of Melbourne and Parsons School of Art and Design, New York.

Researching contemporary art and visual cultures, Les was 2015 Research Fellow at University of the Arts London Research Center on Transnational Art, Identity and Nation (TrAIN) in London. Active in curating and producing museum exhibitions, he has produced exhibitions and public performances in Japan, Brazil, Singapore, China, France and Mongolia and was member of the curatorial team that created the Inaugural Taipei Biennial “Sites of Desire” exhibition and was guest curator at Bikaner House Museum in New Delhi in 2022.

He received his BA (Hons) Fine Art at Central Saint Martins College of Art & Design, MA Fine Art at Goldsmiths, University of London, Masters in Fine Art at Musashino Art University, Tokyo, Japan and M.Sc from Boston University and Vrije Universiteit Brussels Faculty of Economic and Social Sciences. He was awarded his PhD Fine Art from the Faculty of Art, Environment and Technology Leeds Metropolitan University, UK; and Post-Doctorate in Fine Art from the School of Art and Communications at University of São Paulo, Brazil.

Tohoku: Reflections on Memory and Disaster

Les Joynes, Chithravathi (Magazine) Kerala, 2022. A review of Tohoku, Through the Eyes of Japanese Photographers, Cholamandal Artists Village, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. Chithravathi (Magazine) Kerala, 29 July 2022

Tohoku … When we hear this name some of us will be familiar with its location in the rugged northern part of Honshu, the main island in Japan. Tohoku Region (in Japanese: Tohoku Chiho) comprises six Japanese prefectures: Akita, Aomori, Iwate, Miyagi, and Yamagata, and a prefecture we are all familiar with, Fukushima, that was the site of not one, but three nuclear meltdowns at the flooded TEPCO nuclear power station that released radioactive iodine-131 and caesium-137 into the soil, ocean and atmosphere. In 2015 the Kobe Shimbun reported that there were more than two-hundred thousand people displaced. A 2021 report from Japan's Fire and Disaster Management Agency reported the Tohoku events resulted in more than nineteen thousand deaths, more than six thousand injured and more than twenty five hundred missing. A November 2021 report by Japan's Reconstruction Agency revealed that there were a thousand residents still living in temporary housing.

Instead of documenting the anxiety wrought by Japan’s worst nuclear power plant disaster, this exhibition documents the times from 1940s to weeks just preceding the 4-11 disaster. Images display pastoral and bucolic images of village life, the solitude of nature and traditional celebrations that are embedded in traditional Japanese culture. It is the very absence of any reference to the disaster that makes the viewer feel a sense of impending calamity which will befall these often smiling subjects unaware of what is about to happen. Curated in 2012 by Iizawa Kotaro, the exhibition features works from Japanese photographers including Haga Hideo, Oshima Hiroshi, Naito Masatoshi, Tatsuki Masaru, Lin Meiki, Tsuda Nao, Hatakeyama Naoya and the photography collective, Sendai Collection. The photos focus on the historical and sometimes romantic reflections of Tohoku by its inhabitants and by observers.

Through black and white and color photography time is captured as if it is a life-form embedded in amber. To be beheld, turned over and over in one’s hand - something frozen in the moment. Owing to the nature of the mechanism, the photographic frame is selective – and the subjects depicted in their villages seem unaware of our existence seeing them from the future, but sometimes their gaze wanders outside the frame, behind us towards something that even we cannot see. Through the images we feel the solitude and emotional challenges faced by communities living on the fringe of nature.

But what is authentic? And what does “authentic” index? Can authentic mean a favored memory? I am reminded of my own family albums, heavy black leather bound folios kept on a cabinet in my childhood home in Santa Barbara, California. In the early 1960s my mother carefully selected and collaged these photographs into the ivory-colored pages. The photos ranged from 1920s sepia toned stern-faced studio portraits to 1950s and 1960s carefree color snapshots of smiling family members and friends mingled with newspaper clippings highlighting weddings, births, deaths and graduations. As a small child these albums served a point-of-reference for me to identify and locate close and distant relatives both living and dead and put places into a context. They became a touchstone to my own memories. The images were installed in chronological order mapping a sequential experience not unlike that of listening to songs on a record album where when one track finishes we may anticipate in our minds the first bars and lyrics of the next track.

Memories evoked by photographs are themselves constructed, curated, preserved and passed on as a legacy. But memory can be mutated. In the 1990s, my mother then in her mid-seventies set to work to re-curate the albums. As such she created a revised history. New images were added such as snapshots of grandchildren and grandnephews of extended families far away. Images of unfamiliar people were relegated to the end of the final album titled “1977 – present” which had about forty blank pages to spare and these photos were exiled to a kind of photographic paupers field. They became graveyard of photos somehow discordant from the rest living outside the gates appended as an apostrophe that led nowhere. They became a ghost town – the sprawl of development halted in its tracks at the edge of a desert. Other photos were simply removed. Falling into my mother’s disfavor, some family members were excised from the pages leaving haunting white spaces in the yellowing heavy paper sometimes with remnants of paper where the photo was cleaved. For my mother, revising these albums was a therapeutic way to manufacture a different view of history. For me it became simply a different story – one where trauma was omitted. And the more the trauma was hidden the more I thought about it.

The exhibition Tohoku, Through the Eyes of Japanese Photographers then is a construction of a “normal” – the pastoral, the historical, and the quotidian of life in Tohoku. Each passing moment experienced by the subjects captured unaware that destruction would rage through their towns, homes and lives. As observers reading these images in sequence we are aware of the fragility of these moments constructed as if on the edge of a steep cliff. I am reminded of the breath that one might instinctively draw just before and accident.

Chiba Tetsuke (b Akita Prefecture ,1917-1965) shares reflections of local inhabitants that are so idyllic that they could be stills in the early films of Ozu Yasujiro’s contemplative and personal stories. They evoke a feeling that one is observing an idyllic if not “Honmono no Nihon” – an authentic Japan. Kojima Ichiro (b. Aomori, 1924-1964) chose for his subjects villagers and the natural the rough beauty and sometimes forbidding rustic especially in his 1957 photo Twilight, Jusan, Goshogawara-shi which depicts a solitary bundled up villager walking on a rural dirt road in front of a store at dusk evoking a sense of solitude along Japan’s frontiers. The works of Haga Hideo (b 1921 in Dalian. Manchuria) share images of local communities in religious festivals and dance punctuated occasionally with personal expressions of revelers and children facing the camera. Bold temple masks photographed in the 1980s by Naito Masatoshi (b 1938 in Tokyo) document the centuries old folk religions and traditions in Tohoku in particular the Dewasanzan-jinja, a Shinto shrine and pilgrimage site in Yamagata Prefecture. Color lambda prints of larger-than-life temple deities pierce the protective veil and the perceived safety of the museum as if to challenge the observer to awaken and take notice that they are not in a dream. Oshima Hiroshi (b in 1944 in Morioka in Iwate Prefecture presents images of village life, domesticated animals, and one image of an unknown villager, his face blank with a stare that could be that of detachment, surprise or bewilderment. Two images in the exhibition: View from a window, 1959 Morioka and Koiwai Farm 1958 contrast scenes of a funeral procession and a picnic. The funeral procession in View from a window, 1959 Morioka shows two vehicles driving on a gray overcast village street. Black and white framed funeral portraits of the deceased are mounted on a four-wheel escort vehicle which is followed by a hearse. In contrast, the Koiwai Farm family portrait is reminiscent of Édouard Manet’s 1863 painting Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe. It is a portrait of a middle class Japanese family portrait – a father in a suit and tie, children, one dressed in a black military-style seifuku uniform. The family sitting on the freshly mown sun-lit grass gives them an air of insouciance - that everything is, and will remain, prosperous and safe. Standing apart in the exhibitions is a series of saturated chromogenic prints by Lin Meiki (b. Yokosuka in Kanegawa in 1969) created in 2011. These images explore water and flora in deep greens, frozen blues presenting on one side an abundance of nature - and in the context of the exhibition of shy ambivalence. The color works of Tatsuki Masaru (b. Toyama Prefecture 1974) depicting more contemporary inhabitants in Tohoku captured in 2007-2008. These images reflect the direct flash of the camera giving them a sense of immediacy and directness. The subjects nevertheless pose for the images. Some showing a sense of pride and perhaps defiance. The works of Sendai Collection, a photography collective initiatied by Ito Toru which includes photographers Ito Toru, Ouchi Shiro, Kotaki Makoto, Matsutani Wataru, Saito Hidekazu, Sasaki Ryuji and Anbai Reiko include portraits of inanimate buildings in Tohoku: pachinko parlors, soba shops, CD and DVD shops all in a state of stasis if not paralysis. A Japanese artist well known for documenting the aftermath of the 3-11 disaster is Hatakeyama Naoya (b. 1958 in Iwate Prefecture). The images selected for this exhibition however include the “pre-math” (in contrast to aftermath) of the destruction wrought by the earthquake and tsunami – these are captured in picturesque and meditative images of the village of Kesengawa from 2002-2010.

And finally, we see the work of contemporary artist, Nao Tsuda (b. Kobe in 1976) which explores almost formalist composures of winter landscapes compounding an almost suffocating feeling of isolation. His blue-tinged work Kamoaosa, Akita (2011) frames a hillside view of the village in clouded diffused light. The moored boats, like bathtub toys in a blue-chilled sea lay exposed and defenseless. It reminds us that time is almost out – that the event is ascending and all will change forever.

Memory is an elusive conception. How are our personal memories related to and influenced by the overlays of collective memories. How does the photographic image capture, shape and preserve memory and how can those preservations relocate our perceptions of an event. As in the creation of family photo albums memories can be aggregated, curated and mutated. In a photography exhibition like Tohoku, Through the Eyes of Japanese Photographers, images and the captured memories therein, can co-exist in multiple layers containing both trauma and tranquility. As spectators we observe the images in the exhibition intertwined with our own knowledge of the destruction that will transpire. The exhibition enables us to overlay and imprint a new parallel vision – one of calm and tranquility that can co-exist in our minds.

The exhibition visits major cities of India and in 2022 marks the 70th Anniversary of the establishment of Diplomatic Relations between Japan and India. 2022 © Les Joynes

Yoshitomo Nara at Ginza Art Space, Tokyo

Les Joynes, Art in America, 1999

Yoshitomo Nara titled his exhibition "No They Didn't." That's an answer. So it forces a question on viewers of the wall of acrylic-wash-and-pencil paintings that opened his show. They are portraits of wide-eyed or shiftily squinting cartoon-like children with engorged, encephalitic heads. One look at their evil eyes and you know that they did it--whatever "it" might be, from mischievous to monstrous. These "innocent babes" express an inner rebellion bordering on demonic possession. Some of the works.are executed on top of magazine pages whose images and text peep through the paint in that hasty and knowingly naive style currently popular in Europe and the U.S. Like many Western artists, Nara, who has a studio in Cologne, works with binary oppositions.

Les Joynes, Art in America, 1999

Yoshitomo Nara titled his exhibition "No They Didn't." That's an answer. So it forces a question on viewers of the wall of acrylic-wash-and-pencil paintings that opened his show. They are portraits of wide-eyed or shiftily squinting cartoon-like children with engorged, encephalitic heads. One look at their evil eyes and you know that they did it--whatever "it" might be, from mischievous to monstrous. These "innocent babes" express an inner rebellion bordering on demonic possession. Some of the works.are executed on top of magazine pages whose images and text peep through the paint in that hasty and knowingly naive style currently popular in Europe and the U.S. Like many Western artists, Nara, who has a studio in Cologne, works with binary oppositions.

He plays with conflicting metaphors such as high art/low art, innocent/sinister, safe/dangerous in both his paintings and sculptures, and uses symbols and words recognizable in both the West and his native Japan.

One recalls the Diane Arbus-inspired twin girls standing in the bloody hotel hallway in Kubrick's film of Stephen King's The Shining. Nara's tapping into Western horror through the medium of the innocent child is particularly poignant in Japan's controlled society of rigid language and social structures, especially considering recent shockingly violent crimes in Japan involving children as the aggressors. Some people have regarded Nara's work itself as threatening.In the gallery's second room was Three Dogs from Your Childhood, an installation of three identical 5-foot-tall puppies circling an empty comic-style dog dish. They stand on 2-foot-tall wooden stilts based loosely on traditional wooden platform sandals, or geta. Originally Nara intended to perch them on stilts several feel taller, to heighten (so to speak) the conflict between cuteness and danger. However, because of the gallery's low ceiling, common in many Tokyo venues converted from office space, he had to shorten them, so the dogs look more cuddly than worrisome. Other Japanese artists influenced by manga include Takashi Murakami, who creates paintings and sculptures that evoke a sense of a hyperreal cartoon world where floating, big-eyed, grinning characters meander aimlessly through a candy-colored void, and Isuru Kasahara, whose sculptures are troll-like characters. Nara distinguishes himself by merging Western and Japanese concepts to create images that leave the viewer feeling both seduced and perturbed.

1999 Les Joynes © and Art in America/ Brant Publications, New York

A Review of Reclaiming Artistic Research

Les Joynes (July 2020) Journal for Artistic Research (JAR) London review of Lucy Cotter’s Reclaiming Artist Research (2019)

In an age of global pandemic, we have become aware that trusted linear patterns of thinking and expectation must now be reassessed in what is a changed present and uncertain future.

Lucy Cotter’s edited book Reclaiming Artistic Research (2019) is prescient of a need to break with linear expectations and to remember that we can never step in the same river twice. The central ambition of this book is to offer different perspectives from creative practitioners, who reflect on how they use artistic research to further their practices and critique the institutional structures that seek to envelop it. This is a time when artistic research has been co-opted by art institutions particularly in academia through research degrees. This book reminds us that the processes of art cannot be codified, contained or pinned down like a butterfly in a collection. The search in artistic research is intrinsically open-ended – a way forward. This book is not a manifesto but rather an accumulation of dialogues that loosely pique our awareness.

The book is formatted in a way that readers can ‘dip in’ to conversations about how artistic research is being used in practice. The authors present a multiplicity of voices, perspectives and positions and amongst them are Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, Sher Doruff, Em'kal Eyongakpa, Ryan Gander, Liam Gillick, Natasha Ginwala, Sky Hopinka, Manuela Infante, Euridice Zaituna Kala, Grada Kilomba, Sarat Maharaj, Rabih Mroué, Christian Nyampeta, Yuri Pattison, Falke Pisano, Sarah Rifky, Mario García Torres, Samson Young, and Katarina Zdjelar.

Like artistic research itself the book is an open-ended collection of experiences of practitioners using research, which explains how they are sometimes (and rightly) challenging the institutional frameworks that have in the past generation influenced the relationships between artists and institutions. The book does not propose to be a manifesto. It does not offer solutions or next steps but importantly reminds us that artistic research is ever being co-opted and assimilated within universities and other institutions, where now the lenses of research occlude and constrain the very potential of art that artistic research seeks to explore. Through self-censorship and the pervasiveness of professionalization in the industry, artists often explore and present only fragments of the depth of their creative practice.

Three key themes emerge: 1) how artistic research has evolved and the questions that emerge from its often uneasy relationships with universities, 2) how the perspectives of artists research are used as a fecund space for artists to expand and open-end their creative practices, and 3) the spaces of non-knowledge – a theme opened up in the dialogues.

The book’s first interview, with artist Liam Gillick sets the stage for how artistic research has evolved in the 1990s, particularly at the dawn of the Internet and the resulting grab for territory, and with the easing cross-flows of information and the parallel proliferation of texts on art and its relation to procedure. Artistic research engages the work of art outside of its former autonomous Modernist positions and into text, location, and stages. The dialogue reveals how artistic research has been used as a tool to enhance art’s transparency – and in so doing privilege artwork that lends itself to being scrutinized, as if to remove (like the tweaking of a gene sequence) a sense of anxiety. Gillick mentions that while artistic research opens up new spaces in creative practice and interpretation, it also tends to “use artists like parallel institutions to kind of think about it, but not do it” (32).

Gillick and Cotter reflect on how research expands relationships between the material and the virtual – that creative practices have increasingly become immaterial – and it is there that Gillick rightly points out that the added value lies precisely in the sensibilities proffered by artists. This added value builds in tandem with the evolution of new technologies and creative disruption of not only industries but also social structures. They acknowledge that in contradiction to building transparency, artistic research can be used to create layers of complication or confusion. This layering can also create a form of camouflage challenging the observer to easily access what Gillick refers to as the “art moments” and thus creating a “troubling absence” (39) in the work of art. As such artistic research can produce both activities and an environment, which index numerous art moments.

In their dialogue, Gillick and Cotter discuss the emergence of a generation of curators who have seldom or never dealt with artwork materially. As such there may be a privileging of art that can be independently verified through research over art where the leaps are more from associative thinking – likened to that of going through a wormhole to a yet undetermined space in the universe.

Reading this first interview we are reminded that the thing to which art refers may still elude us and continue to exist as something that we cannot directly see. There is a sense that we can map the processes and mine authentic art moments as if they can be teased out, agitated, sifted and gleaned like pieces of gold in busy streams. What does artistic research index then? Is it the authenticity of these signified connections through authentic art moments, to something more empirically tangible? Is it through process that it gains definition? And does this process require definition? Or is it an open-ended search, where something of value might (or might not) appear? Who justifies what artistic research is and does? Is it the artist? The critic? The Research Excellence Framework in universities? And what, where or when is the deliverable?

Once independent and autonomous, art schools now nestle closer and closer into the arms of universities and their academic frameworks. I remember a colleague of mine in London telling me some years ago how he had to defend his art department’s need for studios amidst outcries from the business department’s dean at the same university that “if art students need studios then our business students should have offices.”

And how do artists and curators navigate these churlish currents, particularly in academic environments where knowledge is empirically constructed to drill down, pin-down, and reveal? Since the introduction of practice-led research degrees artists are encouraged not only to plumb new interdisciplinary depths but also to question and challenge current institutional structures.

Artistic research is not only about finding answers or solving riddles - it is also about continuing to pose the questions. Artists by their very nature move into new terrae incognitae – often embracing areas not yet defined by knowledge – areas that are still not yet knowable. Through these interviews we see into the often uneasy relationships between art, other disciplines, and wider discourses. Our attention is drawn to how artists and curators use research as a set of lenses and non-linear lines of inquiry. It shares with readers what they are thinking, their sensitivity to materiality and space. Through their perspectives on the fringes of what we know, we see how they traverse into territories of the unknowable. Through them we peer into areas that cannot be easily defined or characterized, and we share in asking those questions that cannot be answered. We observe suppressed and under-acknowledged hierarchies where Cotter observes the “radical potential lies precisely in the destabilization of reality insisting on this essential incompleteness, a non-closure or non-totalizing of form” (12).

Reclaiming means not only re-affirming what artistic research is and does but also acknowledges its role in expanding the way artists open-endedly engage practice in the 21st century. As a resource Reclaiming Artistic Research invites the reader into the most valuable site of research – the artist’s mind.

Below are synopses of the interviews:

Dutch artist, Falke Pisano uses research to re-path standard forms of representation, exploring the human body in moments of crisis and through this nexus re-examining external socio-political and economic structures. Research becomes a means of evoking something that may only exist through language. Research defines and becomes the artwork where a work of art is constructed piece by piece through its iterations. Pisano also challenges the relationships between the artist and the spectator. Spectators engage bodily with the sculptures, activating their relationship with them as diagrams and introducing the notion that each interface has the “becomingness” and open-endedness of the first marks of a drawing. Approaching this from the perspective of the Deleuzian idea of ‘abstract machines’, the research and art emerge dynamically through repetition in the forming processes of the diagram. Forms are then defined through the amalgamation of these unique and open-ended iterations. (65)

Mario García Torres is a Mexican artist examining methodologies of appropriation, reenactment and re-pathing of structures conceived or initiated by artists of the 1960s such as Robert Rauschenberg, Alighiero Boetti, composer Conlon Nancarrow and curator/researcher Seth Siegelaub. Reinterpreting concepts originating from the past into the present, these investigations continue the thread or re-explore creative conversations. He uses research as a catalyst to recursively re-map, re-contextualize, other and re-familiarize us with art making as it recedes into the past.

While Ryan Gander laments the artwork of the post-Internet generation as sometimes as “fickle and empty” as a free association of signs, he also speaks about the need for the artist to be able to pivot and change. There is a risk that while caught in the re-application of research processes or methodologies the artist may slip into the illusion that they are creating new work whereas they may be only reiterating the same work of art through other means: colors for example. He suggests that the artist has the potential to engage their practice with “loose association” - think like an inventor – invent something new, fail and try again.

Natasha Ginwala speaks of curatorial spaces as sites for artistic research particularly in the Global South, re-examining notions of City, the Village and humanity’s impact on the natural environment. Blurring the lines between the curator and the artist, Ginwala discusses positions from which we claim reference, particularly 19th century spaces for empirical research and findings that examine both the mechanisms of empirical exploration as well as the overseas geographical territories that have prefaced contemporary interpretations.

Lawrence Abu Hamdan is a contemporary artist investigating sound as part of advocacy for human rights and environmental awareness. In his interview he discusses his project ‘Forensic Listening’ and the role of a sound investigator in examining the agency of sound and voice in law. As such his research raises our awareness of sites of epistemic failure. One example, on torture in prisons, considers how the artist and investigator’s role is to construct a language of the sounds in spaces (behind doors, behind walls) what he calls an “Earwitness Inventory” (133).

Yuri Pattison explores how commercial entities are constructing and designing spaces - communal tables in restaurants, forms that communicate an industrial warehouse aesthetic that mirror consumer desire for security. He identifies their sense of repurposing and reclaiming the history, its currency as a form of hackneyed authenticity, owning it like real estate. These spaces often are replicated into networks across geographical boundaries that contain an ad hoc and superficial selection of motifs, signs and signifiers from these past utopian spaces. Pattison goes further to explore the hipness and spatial validation of digital labor and examine open-sourced communities, hack-spaces, open-access sharing models and the notion of how they become gradually monetized, privatized and less-communal. Pattison explores in his installations the manifestation of networks of things that invisibly bind and connect many aspects of our lives – the research excavates the ubiquity of these spaces – picks them apart, teases them open and reveals their existence and connection to the realm of labor and the human

Sky Hopinka, who identifies as a Native from the Ho Chunk Nation, uses moving image, sound, performance, spoken and written language to explore notions of native identity and a sense of “neomythology”. His practice examines the transversal movement between ritual, contemporary poetry performance and film towards spaces of abstraction. He uses tools such as the International Phonetic Alphabet to transliterate and thereby other the Hocąk language to, not only open up new spaces for poetry, but also examine myth and mythmaking and their utility in the formation of the contemporary tribe.

Christian Nyampeta examines the space of translating as a way of revealing notions of identity through his films. As research, he examines how spoken languages evoke identity particularly as addressed by writers and filmmakers within convocation spaces, multi-universe spaces, temporal spaces, and African spaces.

The artistic director of Documenta 13, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev examines the artist’s production, in the age of advanced knowledge capitalism, as alienated cognitive labor. In the 1970s artists explored research particularly as a counteraction to the market dominating tendencies of institutions. This eclipsed the need for a material art and fostered an iconicization of art which then became concurrent with the development of conceptual art, where the image became a placeholder and a currency. On their computers, artists today are similarly, increasingly engaging data as constitutive elements of their working processes. Corporations that must wade through vast amounts of gigadata are working with artists to activate intermediary spaces between data, art and knowledge where their research can pull-back, reframe and widen the perspective of what is perceived.

The practice of multimedia artist Em'kal Eyongakpa’s research problematizes and re-maps traditional Western/colonial filters that observe culture. He explores ethnobotany, sound art, surrealist imagery and other epistemological systems to examine intersections between traditional and spiritual forms of healing, non-Western philosophies and forms of time through the lens of indigenous African cosmology. Specifically, he uses artistic research to explore trans-generational memory through recorded conversations with (Nyang) clan elders. The artist uses metaphor, for example, forests as the Earth’s lungs and the spread of fungus in spaces that represent networks, connectivity and ecosystems. He uses sounds from African rainforests to attune us to sensorial signs of disruption (chainsaws, gunshots in deforestation) that enmesh harmony and rhythms of the ecosystems.

Using “not knowing” as a place of departure for his work, Lebanese artist and actor Rabih Mroué uses his practice to blur the borders between art and theater. sometimes positing himself into fictional biographies and into politically charged situations. He examines non-linear connections, artistic thought-processes as ways to broaden the parameters of what constitutes knowledge – and how pieces of knowledge can have use-value to the artist. Using a variety of strategies often gleaned from theater and performance, Mroué also investigates the liminal spaces between art and history and how artists can use procedures from other disciplines to explore politically charged topics such as armed conflict.

Sher Doruff uses the experimental spaces of writing to tap the conscious and the subconscious, and is particularly attentive to elements that emerge as potential methodologies. Doruff also integrates online images from Google and Wikipedia Commons which often act as nexuses to build new spontaneous directions in her artistic research as demonstrated through the characters in her novels.

Manuela Infante uses theater and performance to enter spaces of “embodied philosophy” where she tests and plays with models of philosophy often free of the confines of academic structures, entering into a realm of the Post Human. She breaks with anthropocentric norms and explores what plant philosopher Michael Marder refers to as a “vegetal other” within us1. It is this othering that pushes artistic research beyond the norms of academic thinking. Through theater she investigates post-identity and transitions out of ingrained gendered roles. Almost reaching towards a form of “botanic synesthesia”, Infante’s work with plants encourage us to think about out human-centric thinking that tends to privilege sentient organisms, exploring the “non-human” and thereby challenging existing attitudes.

Katarina Zdjelar is a Serbian filmmaker who uses video as an art form to explore the limits of language and how it manifests in the human body, exploring for example accent removal and how this creates a sense of altered selfhood. As a research system, art can reflexively pinpoint, isolate and scrutinize elements in our own ‘habitus’ – re-coding what would otherwise go unnoticed. She explores power structures in language, particularly how imposed languages in post-colonial contexts can be used to reinforce forms of identity. She also examines the boundaries between acting and real-life, particularly with actors recreating their own behaviors – akin to semantic satiation when a word becomes othered through repeated utterance.

Euridice Zaituna Kala is an artist and visual researcher from Mozambique who explores how practice can retrace, voice and reclaim the subjectivity of peoples, races, genders, particularly where histories have marginalized their memory. Her interview examines her personal exploration of narratives that emerge particularly from Africa around the slave trade, labor and power, and involve reclaiming knowledge. Distinguished from Western-dominated models of cultural production that have defined colonial era archives and museums, Kala reconstructs narratives that intertwine her experience and imagination and “re-call into existence” a separate experience that questions what history is, what academic research does, and what the artist can imagine.

Grada Kilomba is a Portuguese interdisciplinary artist particularly known for her work on “Decolonizing Knowledge: Performing Knowledge” which challenges our assumptions of the origins and legitimacies of knowledge. Katayoun Arian and Kilomba discuss “registers of knowledge” including printed matter, performances, installations and theory and a departure from the academic towards more open-ended art-based practices. Influenced by her psychoanalytic training she creates performances that tap into the human subconscious and examine symbols through which we construct not only memory and knowledge, but also gender and race.

An artist exploring performance, music composition, archives and drawing, Samson Young explores sound to trigger imagination around historical and contemporary notions of border. Using technology within installations, he unfolds the spaces between music composition, sound and the graphic, where the spectator can meditatively experience the human voice as ‘othered’, and explore how music can be interlaced with certain types of events: specifically geopolitical conflict and collective memory in Hong Kong.

In her speculative fiction, curator and writer Sarah Rifky, imagines a world where art disappears in the 2030s. She uses fiction to create immersive spaces that reflect a growing sense that the current models that have defined the art world are becoming obsolete. Originally taken for granted as time-honored institutions, there is a rise in imitations of the original, such as the franchise created by the Guggenheim and other museums in the Gulf. At the level of institutional critique, Rifky explores the tenability of such institutions to continuously claim value. She instead wonders whether, if works of art were themselves sentient beings, how they would imagine and manifest the world around them. In the context of artistic research this repositions and broadens the scope of language as it is used to define and confine art.

These interviews in Reclaiming Artistic Research shed light on an ecology of creative practices that are using artistic research as a way to open-end the potential of art-making. It also gives examples of how some are using critique, and change how we think about relationships with institutions.

Particularly compelling is Lucy Cotter’s interview with Sarat Maharaj where they discuss the role of “non-knowledge” in artistic research, and processes that make intuition possible – as contrasted to Bergson’s notion of a methodology (196). There is a recognition of the indeterminacy of the “creative moment” as well as the space that is “non-knowledge” – what Bataille called the “other side of knowledge” or what Maharaj calls “cluelessness” (198) on the part of the practitioner, suggesting that practitioners, in the form of bricolage, use artistic research to glean ideas – sometimes superficially – from other disciplines. Referring to Karl Popper’s hypothesis Maharaj comments “we can never know what knowledge is. We can only say we have failed to attain it and in failing, we get a glimpse of what it might possibly be.” (199). Thus, knowledge is approached in the processes of problem solving. One might also infer that to glean from other disciplines is not necessarily to be a dilettante, but may constitute an attempt to construct new narratives, albeit with tools that are not completely understood. Maharaj and Cotter also discuss how artistic research can be a safe harbor for experimentation, risk and failure, moving into what Cotter identifies as “a space for what cannot be named.” (202). Artistic research works as a non-linear space that can freely weave a dialogue with materials and ideas across disciplines – particularly those that acknowledge there are always spaces where we lack knowledge. Research also calls into question what forms constitute a discipline - what is in and what is out - and how it deals with this notion of non-knowledge. Maharaj alludes to the Joycean spaces of “disorder” or the Duchampian “possibility of there being multiple dimensions in which our existence comes to flourish and define itself” (202) Finally, Maharaj speaks of the art academy as something the artist carries with themselves after graduation and something that can be unpacked and shared (209).

Conclusion In light of the past generation’s intellectual developments in technology and social media, creativity has often taken a back seat. Now more than ever contemporary art is expected to be promoted on the grounds of the artist’s intellectual credentials. While maintaining an open-ended creative practice, artists must demonstrate that they can operate effectively within other parallel spaces: the art market, academia, and within systems created through grants.

We are also aware of the professionalization of practice that influences artistic research – groups of students are now referred to as cohorts and their work is defined as a professional practice that gives rise to images of the uniformity and respectability of lab-coated scientists, and yet art-making is often a messy endeavor as we are reminded by Roberta Smith (2007).2 Art as a career choice, as a university department, as a ‘discipline’ is striving for recognition, and so often resources seems to be on the back foot.

Reclaiming Artistic Research presents a cross-section of artists using research not as a way of justifying their practice, but rather as one of many tools to deepen (and open-end) their inquiry and to test and challenge academic and institutional politics, that has resulted in art work often looking packaged and thematized. Artistic research is a relationship – it is a set of tools that can deepen and broaden creative practice, as it is an interface with other systems. Particularly reflecting the ever-present sensation of vertigo in a world radically shifting from materiality of process to a virtuality of processes, artists use research as a tool to produce new syntaxes and increasingly complex works of art and exhibitions.

Reclaiming refers to artists making ‘claims’ for research, as a tool used in creative practices and not only its anticipated reception within broader systemic structures. Reclaiming also means the agency to explore new synchronicities and take unexpected turns, where artists construct areas of thinking that dwell outside of formal categorizations. The authors bring our attention to each creator’s realm of thinking, their sensitivity to materiality, the immaterial, to space and histories. In the interviews we observe how artists can harness the skills and knowledge of diverse teams in forensics, architecture, graphic design, sciences, and the law, to produce exhibitions that index across multiple fields. Reclaiming refers to claiming back the agency of artists within institutional environments, particularly within research degrees in academia. Some institutions have been engaging research as a vehicle for creative inquiry for decades now and some are just beginning to get their footing. Where artists can use research to participate in root-level institutional critique and re-evaluate and challenge the implied contracts with what constitutes knowledge and who are writing those contracts.

This book incites further questions: how can art and these relationships transform when agency is reclaimed? What is the future of artistic research and how can we navigate these complex relationships with institutions? What can we learn from institutions that for the past decades have supported artist-led learning? How can we recognize that this is, and will always be, an uneasy relationship and still continue to create structures that trust and support artistic agency? How can we advocate a way forward towards engaging artistic research in a way that preserves this agency and foments new forms of learning in the future?

Artistic research is coming of age. As a set of tools it interfaces artists within broader interdisciplinary structures. Artistic research is becoming a shared language across the arts, in education and other institutions. Artist research creates new spaces and the opportunity for permutations to discover new forms of knowledge – not plumbing the depths and shedding light on that which is unknown, but exercising themselves in both linear and non-linear spaces that produce insight. Each artist possesses a unique history and experiences that, interfaced with research, can re-map our understanding of what constitutes knowledge.

We are today observing that universities are reassessing and changing how they teach and that museums and galleries are reassessing how they present work. Taking a longer view, we see that these systems are always in flux – and that this ‘uneasiness’ - this reclaiming of agency - is a component of growth and presents an opportunity for us to re-assess these relationships.

2020 © Les Joynes

___________

1.Michael Marder, Plant-Thinking: A Philosophy of Vegetal Life. (New York: Columbia University Press 2013), 186. 2.Smith, R, ‘What We Talk About When We Talk About Art, NYT.com, New York, New York Times, 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/23/arts/design/23smit.html (accessed 20 June 2020)

The Changing London Art Scene: From Conceptual to Romantic, Simple and sometimes Pathetic

Les Joynes, Springer magazine, Vienna, 1997

The late 1990s British art scene sees a shift from the artwork-with- attitude to the artwork that takes on a deliberate tone of modesty, evoking a sense of the day-dreamer, the romantic, and the sometimes pathetic.

The early to mid-90s have been marked by YBAs (Young British Artists) such as Sarah Lucas, Gavin Turk, Sam Taylor-Wood and Damien Hirst whose art has been aggressive, focused on impact and

attitude. Shows such as Freeze (1988, London) and Brilliant! (1995, British artists at the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, USA) and Sarah Lucas’ Got a Salmon on (Prawn) (1994, Anthony d’Offay, London) encapsulate the exportable confident and sometimes arrogant showmanship of British art of the last ten years.

There is a now a move in the London art scene away from the showmanship of the Hirst generation, where the artist became an integral part of the show. Rather than pose as an artist-cum-movie star, more British artists make work that focuses on the artwork alone. The artist, like a craftsman, invests himself in the work where the work stands alone (sometimes dejectedly) without the aura or persona of the artist beside it. Rather than slick media dazzle, more and more artists concentrate on the informal and the modest.

Often they may investigate, as in the case of Transmat (London, June, 1997), the human and sometimes (purposefully) failing or pathetic side of the artist as an individual unable or unwilling to keep pace with changes in society. Young artists in London are portraying this human failing side; as the day-dreamer who wants to live out a romantic illusion. Or, they merely reject the contentious art stance of the early 90s in favor of a more innocent attitude towards expression.

This trend began in the early 1990s with shows in alternative art spaces in London such as Lost in Space (1995-96) at the home/gallery of London-based artist Martin Maloney. Here artists pushed away from the clean, conceptual work of the YBAs in favor of artists who, at least initially, were reflecting the grunge or ‘slacker art’ scene then recently imported from America. This was artwork focusing less on elegance and attitude and more on the anti-showmanship of the Sunday-afternoon painter style of artist.

Recent London art school degree shows (including the Goldsmiths BA and MA degree shows, considered to be the barometer of the London art scene) show an increase in less aggressive and “dumbly profound” work. London art students today are no longer the disenchanted post-punk generation, and are gradually shifting away from aggressive towards more modest art often with an ‘aesthetic for failure’.

In a recent show at London’s leading alternative space, City Racing, British artist David Thorpe showed Riviera Rendezvous (February, 1997 -also showed at Vienna’s Bricks and Kicks Gallery, February 1997). These were cut colored paper silhouettes of romantic settings such as a beach or next to the carnival at dusk where, on the edge of a balcony or on the banks of a river, tiny outlines of couples arm in arm point in awe at a passing shooting star. Thorpe draws upon a lifelong interest in the romantic 1960s films by Eric Rohmer and Jacques Démy to provide a sense of a time gone by when there were simpler pleasures. The landscapes evoke the sense of an artist sitting in his cramped basement studio making modest work with modest materials dreaming of glamorous lifestyles and romantic sunsets. Instead of challenging the London art scene the work evokes a sense of the artist’s personal involvement and reveries.

In other recent London shows including Low Maintenance (Hales Gallery, August, 1997), Transmat (June, 1997) and Beck’s New Contemporaries (September, 1997) British artists including Brian Griffiths and Scottish-born Keith Farquhar are also working with impoverished or modest materials. Griffiths attempts to comprehend a digital society of telecommunications systems, satellite relay stations and space command centers in his recreations of Blue Peter inspired computers using raw, unpainted cardboard boxes which employ water bottle caps and other plastic detritus fixed on with sticky tape as knobs, dials and antennae. One senses that this is the way the artist copes as he sits in his kitchen making home-made versions of the electronics in an effort to comprehend an ultra-fast technology age that has somehow left him behind. Griffiths wants to keep alive the excitement of the modern world - but on his own terms. Likewise, Farquhar is using simple materials such as bright colored markers on white shiny stretched surfaces that look like some kind of flow-chart diagram made on a middle manager’s office presentation board.

These artists are trying (and failing beautifully) to come to terms with a changing world. They find a niche of glamour, of hopefulness in the handmade attempt to recreate totems of reality. Introverted, non aggressive and even sometimes embarrassed work shows a growing trend among young British artists signaling a shift in the tone of the art scene in the U.K. More and more young artists in Britain who are disinterested in the aggressive YBA dominated London art scene are shifting towards the opposite - a more and sometimes even a romantic stance. - 1997 © Les Joynes

Indexing Monument, Memory and Two Cities

Les Joynes, University of Indiana Press (2023)

Slip slidin' away.

Slip slidin' away.

You know the nearer your destination.

The more you're slip slidin' away

Paul Simon (1977)

How can memory be reconciled with absence and change? How can we approach memory of the familiar from the past superimposed with new memories? What happens when the placeholders to which memory is indexed are missing or moved? This essay examines the artist’s experience returning to Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) after almost forty years of absence - in search of Soviet monuments long since removed and discovering they still exist however altered in collective memory.

Introduction

I first visited Leningrad in the former USSR in 1978 and in 2017, I was awarded an artist grant to revisit Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) to explore my relationships with now two cities superimposed with memory– the city, streets, people, statues and explore how monuments (Lenins in particular) remain as markers or placeholders in my memory of the Soviet.

A walk down Prospekt Pamyati (проспект памяти).

In 2017, I was given a flat in Rubinstein Street – one minute from McDonalds, two minutes from Nevsky Prospekt, and a stone’s throw from the Hermitage. For my CEC-ArtsLink project I would be searching for Lenin monuments. I soon discovered that there were few remaining Lenin monuments in the city, at least in the places I remembered his everpresence – even near his apartment in the neighborhood of Petrograd Side. I realized I was looking for Lenin in the wrong way. I discovered his presence had largely been excised from the city’s landscape and placed elsewhere. But the memory of these monuments remained intact in my mind and the minds of residents.

I discovered that my search for Lenin was not a search for the monuments themselves – but a search for the memories. I thus initiated a project to examine the sites of the former monuments and what objects, if any, were placed in Lenin’s stead. My search for monuments became an observation of my own memories, and here in this essay I explore the existence of memory as an “almost” tangible thing.

Capturing cities was not new to me. I had grown up using a variety of film cameras. At fifteen, I began my training under a professional photographer in Santa Barbara, my hometown. I explored how the camera’s lazy eye framed and captured a momentary reflection – an inverted reflection emblazoned on celluloid to be re-lensed onto more chemicals and bonded with paper and light. I began to think and frame my experiences through the terminology of photography as a medium. Learning darkroom techniques I examined how negatives could be overlaid – and I began thinking in terms of the medium.

As human experiences, memories seemed to exist in a blink of an eye, and when captured mechanically with a camera (apparatus-memory) and organically in the mind they co-exist in tandem. At a certain point the borders between human memory and apparatus-memory began to blur. I began to wonder - where was the memory? What was the relationship of the photograph to the memory? So, I brought these questions back with me in 2017 and began to explore how my memories overlaid each other – and what sense I could make of the differences in my teenage memories and my adult memories. Lenin seemed to lean in from all angles.

(Image) Lenin peering in a meeting of the Thirtieth Anniversary of the first Soviet station in the Antarctic. Circa 1986.)

In writing this essay, I realized that searching for Lenin or his monuments, that his politics was not at all my objective. Instead, it became a random walk and discovery on how I (and we) construct for memory museums. It became a means for me to explore what I could learn from experiencing these Soviet and Post-Soviet spaces as layers of memory. As an artist and writer, I could also channel my experiences of these two timelines and my two selves within two cities.

As part of my writing, I use footnotes like a wooden desk uses drawers to store and organize contents. I put them in these drawers as elaborations of my associations with time, memory, places, people and objects.

My relationship to memory and captured image

Just days before commencing to write this essay, a former teacher of mine, then in his 80s wrote to me that experiences (and their memories) give us something to look back on later in life.

I thought about this; memories are the contents of an imaginary film-reel or like a museum visited in our mind. Memories are lenses onto our experiences to be played on demand or triggered by sensations, smells, touch, sounds. We might be transported to a memory of Summer long past, the lugubrious purring of a mower on a lawn and the scent of freshly cut grass filling our nostrils. We are transported back in time. Even a cover photo from a magazine fixes in our memories colors, contours and shapes.

Memories also are fragmented and illusory. Around the age of four, I became cognizant of the relationship between lived experience, memory and photographs. My earliest memories seemed to coexist with the batches of photographs that coalesced when my parents married in 1960. I came to understand that photographs not only trigger memories, but also organize memory.

Photographs, for me, became not only placeholders for memory, but as I would peruse the photo albums they also became the sources of the memories themselves. As placeholders, photographs stood in for the memories. In some ways, photographs became the Platonic Forms to which our fragmented memories attempt to index.

My memories became intertwined with the family albums assembled by my mother. These photographs, taken at a children’s birthday party, for example, came back from processing a few days after the event – while the memories were still fresh. Looking at the images taken from a different perspective (my mother’s) than my own, I superimposed the images (which then became image memory from the albums) with my own as a child-observer. Thus, over the years, my memories were cemented, and the first impressions (mental memory) of the actual event became displaced by the image (photographic memory).

Our experiences as a brief tourist excursion to Leningrad took on an altered memory-afterlife which constructed the images each time I saw them in the family albums. I experienced Leningrad hundreds of times after our brief visit – and as I turned the pages of the album , images of monuments, streets and people paraded in a repeating procession.

“As photographs give people an imaginary possession of a past that is unreal, they also help people to take possession of space in which they are insecure” (Susan Sontag)

It was not only the procession of my experience in Leningrad that was curated: events like birthdays, graduations, Christmas and New Year also gave a chronological rhythm to the albums as a sense of passing of time.

As a family, we fully embraced the technology of the camera. My mother always had a camera in her purse. The first camera I remember was a Kodak Instamatic camera she would take out to snap pictures. The camera was a mechanical member of the family – a friendly mechanical eye that would co-capture the experience alongside our own eyes. It recorded the contours, the light, the toothy smiles, and framed them in a golden rectangle. The camera, I discovered, was part of a ritual of capturing the moment.

Cameras were cheap and processing was cheap. It was on par with having running water and heating or a car in the driveway. My mother did not withdraw a 2-kilo Hasselblad from her purse but rather a slim and inexpensive Kodak Instamatic that had a size of half slice of toast. In their advertising campaigns of 1961, Kodak introduced the term “Kodak Moment,” which further insinuated the camera into the family, lest these moments guiltily go undocumented. Our fragile memories were bolstered by manufactured memory.

As a child, I could not wait to participate in the ritual of photography. At thirteen, I began training under a professional photographer. With camera in hand, I shot thousands of photographs, some quotidian, and others experimental. At age thirteen, from a dusty closet, I appropriated a late 1950s Agfa Silette 35 mm Rangefinder and began to experiment with photographing along the sandy beaches a few miles from my home. Looking through the viewfinder, the images were staged - framed in black like a film-screen in a dark movie theater. Seeing thus, there was some anticipation that what would be framed would be somehow important.

On the beach, however, I was capturing the flotsam that washed up after storms. Just shapes and fragments of things entangled in the beer-bottle yellow-brown seaweed that would wash up in clumps. Through the viewfinder, I was composing a different world that might otherwise exist unseen as abjected detritus – I was somehow memorializing the mundane and the ordinary, and, in the process of printing and showing it, putting these images awkwardly in a frame.

It is no wonder that we take and accumulate so many photographs when we travel. When the travel was over, the photographs became touchstones – refreshers to tether me to the illusion that there was somehow a sense of authenticity of the photograph to the memory. Perhaps, this search of proof of the Real is an attempt to bind and control reality. Perhaps, it is our very human nature to bolster recollection as without it we may feel lost, or worse, banished.

With camera in tow, I discovered that seeing is curated. I began to capture how sites and objects were affected by time. How there was a story revealed in their disappearance.

Recollection, image and archive: the family albums

My memories, including those of my experiences of the Soviet Union archived in photo albums. In 1959, my mother began a series of “Books” - a set of seven heavy black leather bound folios kept in a deep cabinet in my childhood home in Santa Barbara, California. For my mother, the camera and film processing were more of a utility than a luxury.

Our roles of film were processed at a camera store called Anderson’s in my hometown, Santa Barbara. The store was a canyon of stacked yellow-labeled carton boxes of film and rows of cameras lining the walls like hunting trophies.

After a few days of processing, my mother and I would collect a pile of fat envelopes brimming with freshly printed glossy photos still smelling of development chemicals. Back in the car, my mother and I would peak at the images. When we arrived home she would deposit the packs of envelopes into a cardboard box with felt tip lettering “for the Books” which was placed in a cupboard. There that sat for several months.

Twice a year, my mother drew out the envelopes from the box and spread them across the dining room table. Pictures of me theatrically hamming for the camera and those of family or friends smiling with their eyes closed were cut from the deck and reinserted, like errant thoughts, back into their envelopes with the negatives. The selected images, like newspaper clippings or holiday cards, would then be collaged into the timelines of events. Once the images were affixed with white paste, my mother would then take a blue fountain pen to write in her round flowing script any dates and pertinent details of who, what, when and where onto the grey-colored card-stock pages of the Books.

There were about eighty pages per folio and six folios, each embossed on the spine with “Book One”, “Book Two,” etc. in gold lettering. Book One had images from before 1960s, Book Two for the 1960s, Books Three to Six were the 1970s after 1977 they stopped and Book Seven lay fallow and was never used.

My mother was curating memories. Book One included a multitude of sepia-toned studio portraits taken before World War II from people I had not met in person, many of whom no longer living or living far away. In Book Two, there were post-war carefree green and blue hued color snapshots of smiling family members and friends mingled with Christmas and birthday cards, newspaper notices of weddings, births, deaths and graduations. Like looking within a recursive set of facing mirrors, there is an image of me age four looking at images of me in the Books.

The author, age 4, in 1967 investigating Book 2. 2022 © Les Joynes and ARS New York

These photo collections, and their ordered sequences in which they were presented, would document and parallel my own memory as I grew up. They served a touchstone to identify and locate close and distant relatives, both living and dead, and put places into a context. They served to index my own memories.

The photos, were sometimes otherworldly, especially those from the 1950s, where snapshots were color-saturated in the greens and reds – which became even more pronounced over the years, so that these images (and memories) became othered.

Evoked by photographs, memories can be constructed, curated, preserved, and shared. There was one set of photos in Book Three that evoked a restaging of another photo. In 1958, my mother took a photo of my father sitting on a low cypress tree branch near the ocean in Carmel, California. For them this was an iconic visit. The photo of my confident grinning father became a touchstone to the visit. Twenty years later, the scene was restaged with my father and my brother and sister-in-law – and the images were re-curated in the album with the original photo at the core and radiating the reflections. This restaging in 1978 became a commemoration not only of the event but also a performance of the photo.

Image of the author’s father in 1978 reposing a photograph taken in 1958. 2022 © Les Joynes and ARS New York.

We are tangentially linked to the Soviet through images from other countries. The images of the Soviet were cemented in memory not only in my visit to Leningrad but also through books, television on CBS news in Time, Life, Paris Match and other magazines. The Soviet was top of the news in broadsheets in the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. It is even rekindled for me when I see contemporary images of Victory Day Parades in Moscow, Military Foundation Day parades in Pyongyang, and in Beijing Chinese National Day parades.

Image: Official demonstration on 7 November 1977 on the Red Square in Moscow, 7 November 1977. Photo by Szilas.

Memory and Image can be mutated and reconfigured. Not only can photographs be restaged and re-curated, they can also be disappeared. In the 1990s, my mother, then in her mid-seventies, set to re-curate the albums. She created a revised and parallel history. Falling into my mother’s disfavor, some family members vanished from the albums. Their photos were excised from the pages leaving haunting white spaces in the now-yellowing heavy paper, sometimes with remnants of paper where the photograph was cleaved.

For my mother, revising these albums was a therapeutic way to excise trauma and manufacture a different view of history. And the more the trauma was hidden, the more I thought about it.

In Book Six, new images were added, such as snapshots of grandchildren and grandnephews I had never met. Some photographs were of children I did not know existed, they being born from extended branches of the family thousands of miles away. I am quite sure my mother had not met them either. Perhaps, it was an act of public record. But, I am quite certain, these photographs were, for the most part, generic placeholders for the blank spaces from her purges. These images were not memories. They were placed outside the gates - appended as an apostrophe that led nowhere. Their territory became a ghost town – a sprawl of development. A potter’s field halted in its tracks at the edge of a desert.

The end of the albums marked for me a chasm where the memories just stopped at a cliff. While there was a perfunctory endeavor to manufacture a whole (even with parts that are unfamiliar). I had discovered where photographic image and memory and for me the Books stopped making sense.

My First visit – Leningrad 1978

When I visited the city for the second time in 2017, I realized my memories of Leningrad were intertwined with looking at photographs from the family albums and from thirty years of impressions from the popular press.

The album photos have all faded with time. The colors have skewed red in some, blue in others. In Leningrad, my mother and I took turns taking photos. In contrast to the Agfa rangefinder, in which light settings needed an external meter, and focus needed to be set manually (and the lens cap needed to be removed), the Kodak instamatic is a no-brainer. Apart from lining up the subject in the square viewfinder, the Instamatic kept most everything in focus.

Image of Kodak Pocket Instamatic similar to the one used by the author’s family.

The Pocket Instamatic’s 110 (13 mm × 17 mm) film format is much smaller than 35 mm and the images seemed more grainy and blurry. As I have written this essay while overseas, I have gleaned the internet for photographs that approximate what I remember from the Books.

“Nevski Prospect, Leningrad 1970”

The Hermitage in the 1970s.

In August 1978, Leningrad was hot and muggy. The air was still and humid as if made of gelatin. Driving by in the Intourist bus in late afternoon, golden sunlight struck the stern blocks of buildings and dusty trees. The Hermitage loomed large. Visiting a museum was a familiar operation that brought some sense of order to experiencing a new city. It was part of a ritual that went hand-in-hand with being on a tour bus to see monuments, parks and buildings, as well as sampling local cuisine and listening to local music. For the tourist, these rituals codify the unfamiliar, making it palatable and appreciable. For me, most interesting was the sense of experiencing the other – living and breathing in a different world. Still, the Intourist guides were stern and always careful that we did not stray from the group. There was a hosting methodology of keeping us moving forward – no dawdling and certainly no speaking with locals. It was choreographed.

Vista in Leningrad in the 1970s

Visiting the Soviet Union was an opportunity to peer behind the iron curtain to see beyond what was depicted on television, in the press, in literature and in films. Perhaps it was a modern form of Big Game hunting. Where the big game was the rush of capturing - “gestalting” - with one’s own senses being present in history. Or perhaps it was an experience as described in the Kantian Sublime where one steps out into a storm. For me it was theatrical. It was like visiting another world.

In the 1970s, there seemed an abundance of soviet monuments and the sheer monumentality of the city. I recall out of the corner of my mind a Lenin on every corner. I realized when I returned in 2017, this was an exaggeration and my own photograph-constructed memory.

Trams in St. Petersburg in the 1970s.

In Leningrad in the Seventies, the light seemed different, the green, defiantly-broad officers uniform caps adorned with red and gold seemed curiously from a bygone era and yet menacing. Perhaps this was indeed where Europe met the East. This was my first East.

Memory itself was somehow softened through repeated washing and pressing and folding. It was compressed paper-thin into coffee table books and into the frames that adorned walls of museums. In these images, often depicted in paintings or lithographs, time seemed distant and unreal resting innocuously behind a veil – staring from across a river that separated them from our then 1978 Kodachrome color present.

Poster circa 1960s “The country of workers and peasants is storming the stellar ocean!”

In the 1970s, the USSR felt to me like a delicate subject, almost taboo, which made it even more enticing. Blockbuster films like David Lean’s Dr. Zhivago (1965) based upon Boris Pasternak’s 1957 novel, gave a palatable and even romantic version of Russia – a perhaps friendlier and old-world stand-in for the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. Russia for me was the idyllic 19th century from which was born a behemoth power machine of military armament, Sputnik and Five-Year Plans seemingly created out of sheer will.

On my second day in Leningrad in 1978, my family and I were in a chrome-trimmed emerald-green tourist bus being driven with other foreign tourists along Nevsky Prospekt. I remember, out of the corner of my eye, a flotilla of buildings basking in the stagnant humid August summer day accented with flags. Flags fluttered at regular intervals, like polka dots, accenting the beige stone facades, while convoys of fat grey diesel trucks growled slowly towards the river to cross the bridge to Petrograd Side.

I peered at the cars on Nevsky Prospekt. They were different – more European and more compact – puckered matchbox Ladas in dark green, beige and white comingled with the occasional bloated black Volgas for officials, the hot sun gleaming on their polished black roofs and hoods.

Like a train of crawling centipedes, turquoise, red and beige colored trolleybuses crawled in no particular hurry up and down the streets. Their spring-loaded trolley poles rubbed the overhead electric wires with the occasional spatter of electricity. These were Soviet examples of the streamlined European Modern conveniences emerging from the Second World War. Leningrad appeared as a mélange of Haussmann-era bourgeois opulence and embellished with clean-edged Sputnik tones.

Trolley buses in Leningrad, 1970s

Advertisement for the Hotel Leningrad late 1970s.

Featuring the story of Laika the Space Dog in 1957 on a Emirate of Ajman postage stamp.

I had seen glimpses of the Soviet Union in the popular press in America – black and white images followed by two-page spreads of colorful parades of green-clad peak-capped soldiers and young women wearing Russkaya kosa braids merging with the diversity of the Soviet Union on parade. These memories of looking at photographs overlaid what I was seeing in 1978.

Image TIME Magazine Cover: Kosygin, Khrushchev, Stalin and Lenin - Nov. 10, 1967.

What I was seeing from the bus window was real – it was neither a film nor a photograph. These were real people. And although Intourist kept us on a short leash, I felt I was able to see a stratum of the quotidian in Leningrad.

Image A children’s playground, Krasnoy Konnitsy (Red Cavalry) Street, Leningrad, 1978.

Leningrad’s Hermitage, like all museums, was a destination. Paintings and sculptures, particularly western masterpieces, were themselves talismans to the familiar. The artwork displayed in the Hermitage’s palatial galleries were a feast for the visual consumption of Western European art. Familiar. Almost. It was uncanny. As a teenager I then beheld the fierce behemoth eighteenth century palace. Unlike Fontainebleau, which was set back surrounded by gardens; the Hermitage was constructed to be viewed publically.

The Hermitage was (and is) urban. It contours its spaces to maximize the fit along the Neva River. Approaching the Hermitage for the first time from the front, I peered at the central triumphal arch of the General Staff building - my eyes rolled up and around inside, like a giant hole in a block of Swiss cheese; the cavernous space itself was the monument dwarfing and engulfing me.

Archive photo of the Winter Palace and Alexander Column from the arch of the General Staff Building, St Petersburg.

Where was Lenin?

During the 1970s, I found most curious about Leningrad were the monuments – I seemed to remember mostly Lenin. Black bronze giants on pedestals. Pale saffron Beaux-arts classical homes draped with red flags in front. Lenin’s portraits adorning schools. Crowds thronging outside the Dom Knigi bookshop. Beige trams clogged the streets, their bow collectors scraping the overhead wires as if with a giant violin. Sculptures of red hammers & sickles and posters of grasping hands of comrades. The endless vista of Nevsky Prospect.

By far, the most impressive Lenin was the Constructivist inspired 1926 statue, created by sculptor Sergei A. Evseev, of Lenin at the Finland Station. The sculpture captured Lenin, right arms and hand extended, giving his 1917 homecoming speech atop of a plinth inspired not by an equestrian statue of bygone days but by the pill box top of an armored car. In the late 1970s, there was a rush to place a Lenin statue at every station in Leningrad.

Statue of Lenin at Finland Station

Image from May Day circa 1977.

There were many Lenins: Lenins that look like Lenin, Lenins that look like Siberians, Big Lenins, Small Lenins on stamps and pins, mature Lenins and even Young Lenins, In 1978, my mind was superimposing images of Lenin from magazines which displayed giant Lenin heads. Images that seemed to (but not quite) index the image of Lenin from films like Dr Zhivago. Some Lenins, I remembered, seemed nearer to life-size as if “one of us” - they stood over us on tall pedestals.

Was I hallucinating Lenin? Where did the layers having glimpsed Lenin in some form or other invade my fifteen-year-old experience? Lenins festooned in my mind like some fantastical stamp collection. Lenins were here and there from Petrograd Side to Yalta all the way to Ulan-Ude in Buryatia in Eastern Russia. The Lenins haunted me. They permeated my memory – Lenin was a familiar character in a memory play –we knew him by many forms. At that time I was not looking for Lenin – he was just everywhere it seemed. The Intourist guide, a prim middle-aged woman with blond hair tied in a bun, gestured mechanically in swooping motions to the monuments and shouted into the bus microphone.

“On our right is Moskovsky Prospekt….and here is our new statue honoring Comrade Vladimir Lenin ….and Behind this is the House of Soviets ….build in the ….1930s….unique style….glory of the Soviet people…..”

It was hot – the air muggy and still seemed to press in on our perspiring bodies now stuck to the back of the vinyl seats. I was fifteen and was not used to sitting so long. My mind grew foggy in the tepid heat. I pressed my face against the domed glass on the tour bus and felt the engines rumble over the bumpy streets. My face flattened against the window, my eyes peered up and down to watch the cascade of scenes accompanied by the now garbled sounding tonal swings of the guide.

Image: Lenin Monument unveiled in 1970 on Moskovsky Prospekt. by the House of Soviets behind him which was built between 1936 and 1941 in the architectural style known as Stalinist Empire.

Sculpture of Lenin at Smolny in Leningrad by Vasily Kozlov (1887 - 1940)

On the bus the monuments, squares and prospekts fleeted past. Like exclamation points on strategic corners and plazas – and the city punctuated by Lenins in all shapes and sizes.

How did I as a fifteen year-old perceive monuments? At that time the monuments seemed to possess something. A sense of historicity perhaps.” As an artist who creates assemblages, I explore memory associated with objects. For me, there are also “material memories” that we project onto found objects, sites, buildings. So, as a fifteen year old I projected everything I had learned about the USSR into these monuments. And because there were so many of them. and most of them so much bigger than life, for me they mirrored the anxieties of the cold war. Leningrad thus became, for me, a museum - a place of observing something that is transgressive and forbidden. In my teenage eyes, I felt the “other” in the monuments - and my own “otherness’ as an observer.

Memory compounding: How memories of St. Petersburg superimpose on those of Leningrad.

Sandwiching four decades, my dual visits to Leningrad and St. Petersburg felt like visiting a museum, or perusing a family album. Experiencing a city that has transformed over the years engages us with an overlay of memories - one on top of the other, and a re-indexing and recalibration of ourselves to experience the transformed city.

When something is moved or changed, there is a certain vertigo – a fleeting sensation of the uncanny and weirdness when these two images - one from our mind’s memory and one that stands before us - are somehow reconciled as they coalesce.

At first, memories seem to exist as fact – like a film reel. Then, over time, the memories may begin to float untethered and dis-membered, mingling like weird images from superimposed color film negatives. Our mind sets to work immediately to reconcile the differences. We look at a friend we have not seen for thirty years. They have grown older. But our friend’s eyes and certain mannerisms are the same. When we observe a city, or our friend, all the memories of the past and what we are now seeing are compounded and membered, reconciled, harnessed and collated again into a new 3.0 update. The new compounded memory reconfigures the person, site, or thing. They have not lost the prior versions – they are embedded in our minds like photographs embedded in a family album. They are an amalgamation of our experiences of them over time – we just recognize the latest version as the one with which we interact.

Perhaps that is what my memory of Leningrad feels like: a dissolving of form. It is like saying, “I never took notice of it until I realized it was disappearing.” But it is precisely the going-ness that is interesting to me: a sense of transience and indeterminacy.